Blog post by Joshua Boydstun, Rabbinical Student at Reconstructionist Rabbinical College

——————

My camping tent has seen its fair share of adventure: Caked in the red dust and baked in the summer sun of the Sonoran Desert. Encrusted with the frozen rain of a Yellowstone autumn. Rocked with rain, whipped with wind and sprayed by a skunk while the remains of Hurricane Ivan swept through Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Plateau. Yet through it all, my seam-sealed tent has remained safe and secure, warm and watertight. I’ve enjoyed the pleasures of living in the wilderness while avoiding most of its discomforts.

My camping tent has seen its fair share of adventure: Caked in the red dust and baked in the summer sun of the Sonoran Desert. Encrusted with the frozen rain of a Yellowstone autumn. Rocked with rain, whipped with wind and sprayed by a skunk while the remains of Hurricane Ivan swept through Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Plateau. Yet through it all, my seam-sealed tent has remained safe and secure, warm and watertight. I’ve enjoyed the pleasures of living in the wilderness while avoiding most of its discomforts.

The Jewish festival of Sukkot, a week-long holiday beginning on the 15th of Tishrei (September 18-26, 2013), delivers a very different experience. The traditional practice of building and residing in a sukkah (“booth”) derives from Leviticus 23:42-43:

You shall live in sukkot (booths) seven days; all citizens in Israel shall dwell in sukkot, so that your descendants will know that I made the Israelites live in sukkot when I brought them out of the land of Egypt—I the Lord your G-d.

The sukkah cannot be just any structure. According to halakhah (Jewish law), the booth must satisfy numerous requirements regarding its dimensions, design, materials and placement. For instance, the Mishnah—a second-century compilation of rabbinic laws—states that “a sukkah that is taller than twenty cubits [approximately thirty feet] is invalid” (M. Sukkah 1:1). A reason for this prohibition is supplied by the Gemara, a later rabbinic commentary on the Mishnah:

Rabbah explained: “Scripture says, ‘So that your descendants will know that I made the Israelites live in sukkot” (Leviticus 23:43). [In a sukkah] up to twenty cubits [tall], one “knows” that one is dwelling in a sukkah. [But in a sukkah] taller than twenty cubits, one does not “know” that one is dwelling in a sukkah, since one’s eye cannot see it. (Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 2a)

Likewise, a valid sukkah must possess the right balance of sun and shade (Sukkah 7b), and its covering must be made from particular types and arrangements of natural materials (Sukkah 12a-14b).

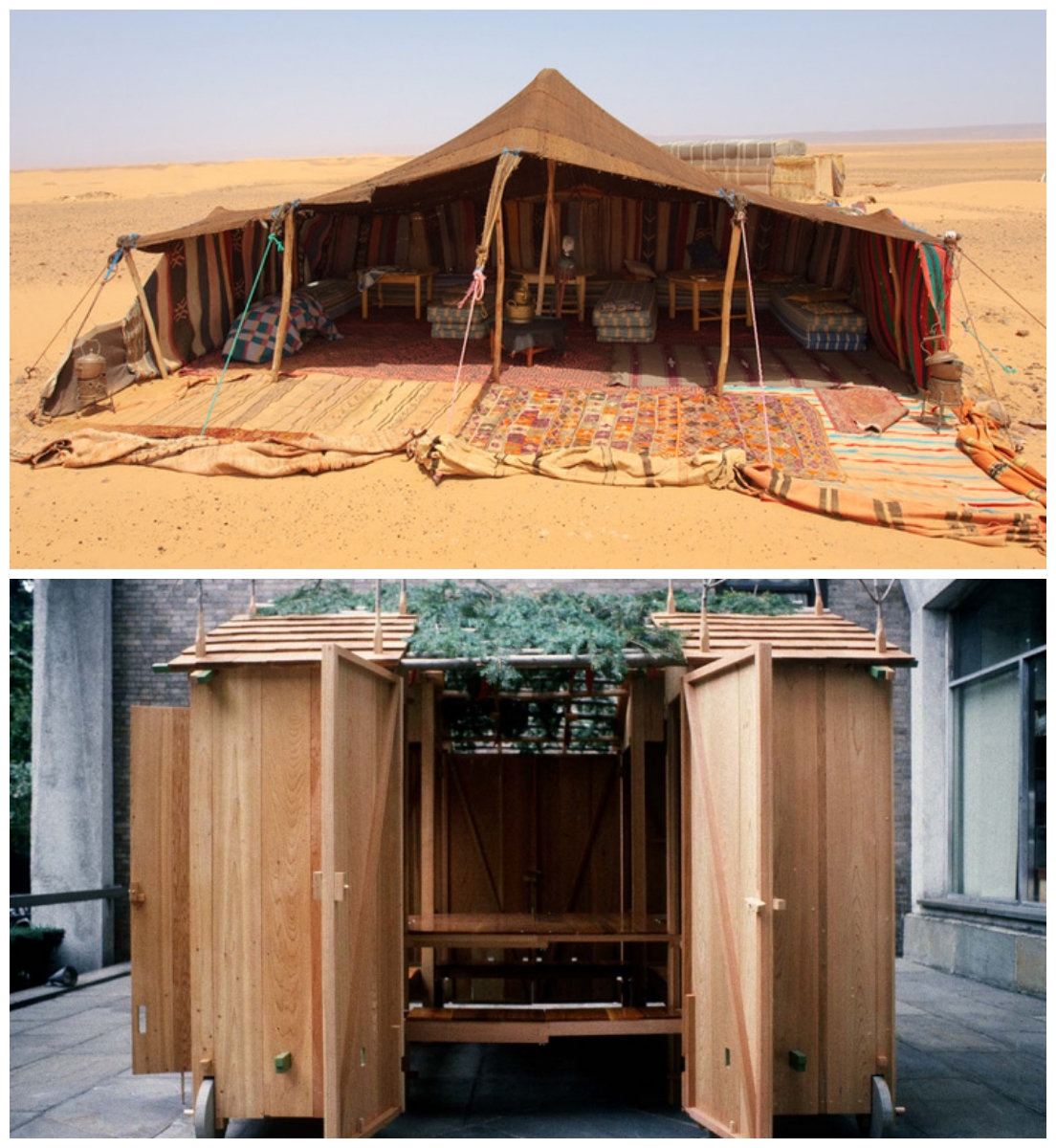

As one might expect, a sukkah is not always the most comfortable shelter. The Mishnah requires that for the entirety of Sukkot, “the sukkah becomes one’s permanent dwelling, while one’s house [becomes one’s] temporary dwelling.” Even if it rains, one cannot seek shelter elsewhere unless the rain is so heavy that it spoils one’s porridge (M. Sukkot 2:9)! At the same time, however, the Talmud declares that one should bring into the sukkah any fine dishes or furniture that one may own. This way, one can eat, drink and relax in the sukkah as one would in one’s regular home (BT Sukkah 28b).

The sukkah is full of contradictions: It is a temporary structure that should be treated like a primary home. It is a thatch-roofed hut with fancy furnishings. It is a place where meals are served on fine china, but where rain must be tolerated unless it spoils one’s food. In short, the sukkah is the ideal structure for reenacting the exodus from Egypt in all its complexity. It is simultaneously liberatory and terrifying, wondrous and grueling. When we step into a sukkah, we blur the boundaries between past and present, wilderness and civilization, hardship and comfort, passion and complacency, vulnerability and safety. We discover nature by inviting it into our home.